The cleaning workload must be considered in its entirety

Cleaners and supervisors feel that their work is very meaningful. However, they experience physical and psychological stress, which is also influenced by the working environment.

If you google the words “good ergonomics” in an image search, you will get pictures of a worker sitting at a desk. The images show how to ergonomically adjust the desk, chair and computer screen. This is useful information for office workers, whether they work in a private office or in a shared office. He has the opportunity to influence his own working position, but what are the workstations of a cleaner like from the ergonomic point of view?

A cleaner can rightly be called a multi-space worker. The workplace changes several times a day, and the cleaner has no control over the ergonomics of the working environment. However, the working environment also has a significant impact on the ergonomics of cleaning work. These include the condition of the premises and surface materials, furnishings, the cleanliness and tidiness of the premises, air conditioning and waste management.

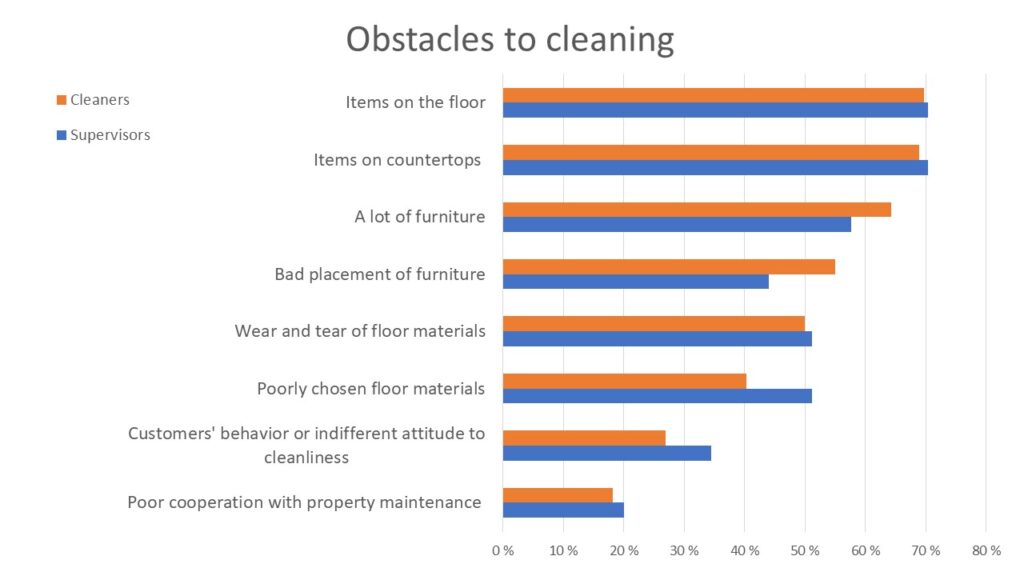

In the ErgoClean project, surveys were carried out to find out the experiences of both cleaners and supervisors about the factors that hinder cleaning at work sites. Both cleaners and supervisors agreed on the factors that hinder cleaning (Figure 1). The main obstacles to cleaning were the amount of goods on tables and floors. Around 70% of respondents felt that the amount of goods prevented efficient cleaning. Many had also identified the large amount of furniture and its awkward positioning, as well as flooring materials unsuitable for the use and consumption of the space and their wear and tear as obstacles. Around one in three respondents had found the customer’s behaviour or indifferent attitude to cleaning as problematic.

According to respondents, their employers are making efforts to improve safety in the workplace, but this alone is not enough. Cleaning is often an outsourced service, so cooperation with the client organisation and possibly other outsourced service providers is needed to improve safety and ergonomics. According to the survey results, one in five respondents felt that cooperation with the building maintenance service was poor.

Figure 1. Percentages of all respondents reporting various factors that hinder cleaning and reduce ergonomics.

Musculoskeletal disorders in cleaning work

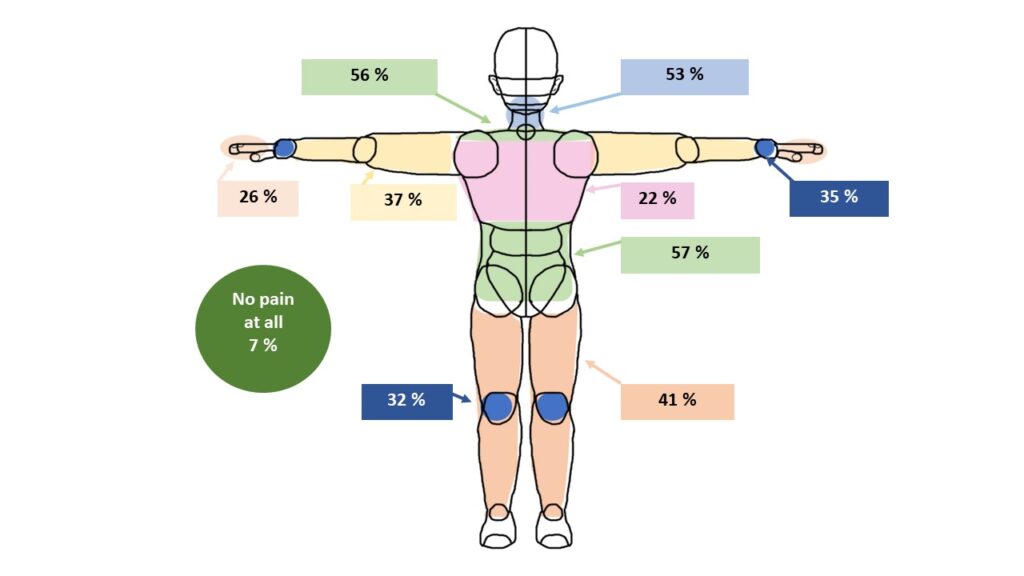

We know that musculoskeletal disorders are common among cleaners. The cleaners who responded to the survey reported experiencing pain, particularly in the lower back, shoulders, and neck (Figure 2). More than half of the respondents experienced pain in these areas of the body. Pain experiences were higher among older respondents.

Figure 2. The percentage of cleaners who had experienced pain in different parts of the body.

The EU’s Healthy Workplaces Lighten the Load campaign lists the potential risk factors for developing musculoskeletal symptoms.

These include biomechanical and work environment factors, as well as organisational, psychosocial, and individual-related factors.

Biomechanical and work environment factors include stress caused by carrying, lifting, poor and static working postures, which are also present in cleaning work. Organisational stress factors include rush, long working hours, monotonous work, and lack of breaks. Psychosocial strain can arise if the worker has little control over his or her own work and workload, if the work is emotionally demanding or if there is a lack of support from colleagues and supervisors. The onset of symptoms is individual and influenced by factors such as age, physical performance, health, and weight.

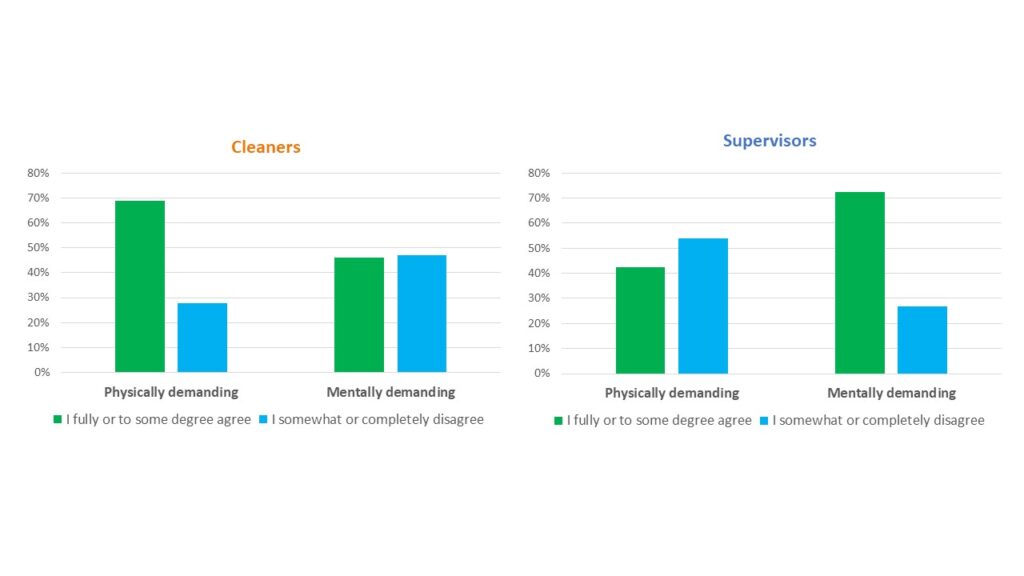

According to surveys, 70% of cleaners found their work physically stressful and 70% of supervisors psychologically stressful (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cleaners’ and supervisors’ experiences of the physical and mental strain of their work.

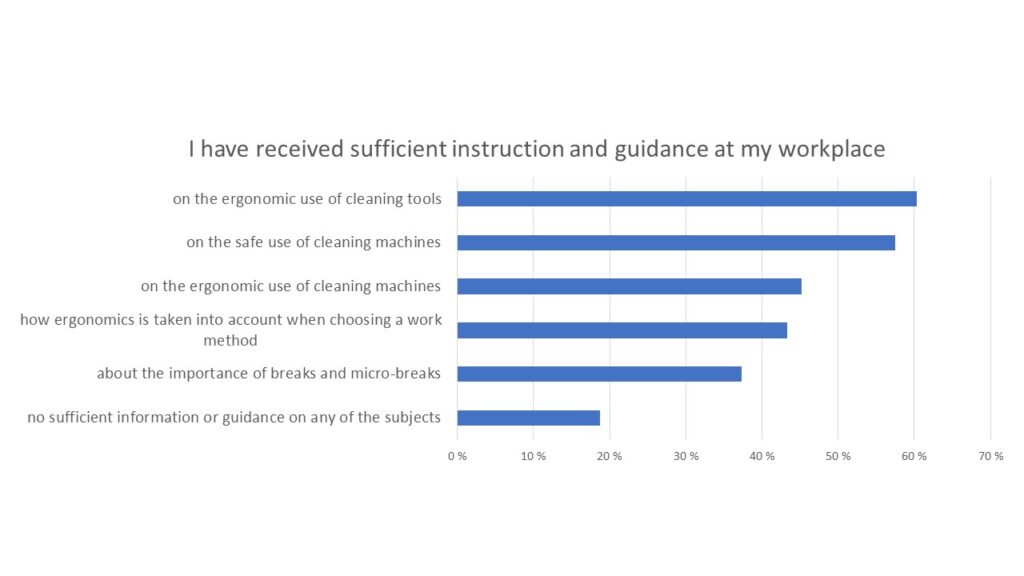

The physical stress of cleaning work is influenced by the choice of tools and methods. The decisive factor is the cleaner’s ability to choose the best possible tools and methods for different situations. Professional skills and on-the-job training play a major role. Cleaners were most satisfied with the training they received in the use of cleaning equipment (Figure 4). 60% of respondents felt that they had received sufficient guidance and instruction on the ergonomic use of cleaning tools. The importance of breaks and micro-breaks is not sufficiently explained according to the survey. Another worrying result is that one in five cleaners had not received sufficient guidance on any of the topics asked.

Figure 4: Cleaners’ experience of the adequacy of ergonomics-related training in the workplace.

Experiences of work and psychosocial stress

How do cleaners and supervisors perceive their work? According to the responses, it’s a pretty good job. 93% of cleaners and 97% of supervisors considered their work to be meaningful and 54% of cleaners and 75% of supervisors were always or often enthusiastic about their work.

Respondents perceived their own work as diverse and varied (61% for cleaners / 89% for supervisors) and independent (81% / 82%), with support from both colleagues (77% / 84%) and supervisors (75% / 75%). According to respondents, information is shared in the workplace in a reasonably open way (59% / 71%). There is room for improvement in terms of equal treatment of staff, as only 57% of cleaners and 68% of supervisors felt that they were treated equally. More than half of respondents were confident that they would keep their jobs (63% / 70%).

Surveys show that supervisors have more influence over their own work than cleaners. One in three cleaners felt that they had no influence at all on the content of their work, compared with only 6% of supervisors. 39% of cleaners and 20% of supervisors had no influence at all on where they worked.

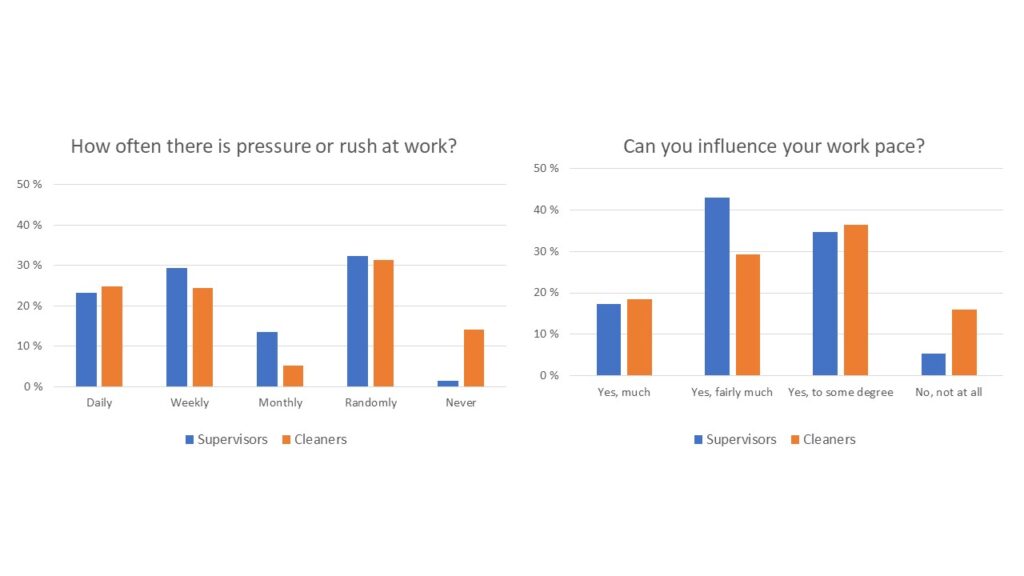

The surveys also looked at how busy the cleaners and supervisors felt at work and what they could do about it. Around one in two cleaners and supervisors felt busy on a daily or weekly basis. On the positive side, the majority of respondents felt that they could influence the pace of work at least to some extent (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Cleaners’ and supervisors’ experiences of being busy and having an influence on their work pace.

The results of the surveys will be used to design the content of the guidance materials to be produced by the ErgoClean project. The aim is to develop materials for ergonomic training in cleaning and for the prevention of the most common occupational diseases and accidents.

The surveys were carried out in November 2022 in Finland, Estonia, Hungary, and the Netherlands. Surveys were sent to ten organisations in each country and were answered by a total of 267 cleaners and 147 supervisors.

Tarja Valkosalo

Propuhtaus